- Home

- Emily Brewin

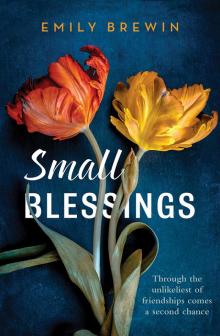

Small Blessings

Small Blessings Read online

The wound is the place where the Light enters you.

—Rumi

To my parents, Helen and Michael Brewin, with all my very best love.

First published in 2018

Copyright © Emily Brewin 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 226 7

eISBN 978 1 76087 053 9

Pages 18, 98: extracts from E.M. Forster, A Passage to India, ed. Oliver Stallybrass

(London: Penguin Classics, 2005)

Cover design by Julia Eim

Cover photo: Magdalena Wasiczek / Trevillion Images

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Contents

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie & Isobel

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Isobel

Rosie

Acknowledgements

Rosie

THE NIGHT SKY IS SPILT INK as she steps off the train. She stands for a moment and stares up at it. The station’s deserted, and for once in her life there’s a sense of space. It stretches out, a rubbery band, all around her.

She’s hardly ever alone. Living in the flats is like living in an ant nest, people scurrying around all day and night. And there’s always fighting. The couple in the flat next door are the worst. One night last week the wife screamed so bad Rosie called the cops, something she usually avoided. But the screaming brought back memories, and she didn’t want the woman on her conscience.

The husband’s a pig anyway, covered in roughly drawn tatts and body hair. He’s been inside for sure; there’re prison tatts up his arm. He leers at Rosie whenever he gets the chance and frightens Petey. She doesn’t like ratting but the dickhead had it coming.

The air’s cold and a bell further down the tracks warns of another train.

She follows an overgrown path away from the station onto the street. A couple of the streetlights are on the blink, making the road darker than it should be. It doesn’t bother her though. The night’s nice to be wrapped in.

The little cottages along the street are dark too. The whole area was working class once but then the yuppies moved in and renovated all the houses, extending them up and out at weird angles so it’s hard to imagine what they look like inside.

The flats come into sight as she rounds the corner. Petey’s backpack rubs her shoulder and she can hear herself breathing. It’s strange, listening to the air pumping in and out of her chest. She pulls the hoodie over her hair and shoves her hands in her pockets. A cat leaps out from behind a wheelie bin and scares the shit out of her.

‘Jesus.’

She sidesteps then walks faster towards the flats at the end of the road.

Suddenly there are footsteps behind her, cagey and quiet. She stops and spins on her heels but no one is there. She glares into the darkness then turns and walks on, focusing on small landmarks ahead, the give-way sign at the intersection and the red sports car parked up the kerb, to lead her home.

More footsteps.

She begins to jog despite herself, the pack bouncing off her shoulder. Slow at first, then faster because she can’t help thinking of the phone call this morning and the parole date she knew was coming. The air whistles past her head, stinging her ears, making her wince. Panic prickles her skin. She should look, but she hasn’t got the guts. She stumbles and Petey’s backpack slips to the ground. She clambers up and runs again. She should stop, take a breath, be brave, go back and pick it up. But a steel curl of memory tells her to bolt. Now she’s got too much to lose.

She doesn’t stop until she gets to the fence bordering the flats. For the first time in a long time she’s glad to see the towers looming above. The shitty brown façade with rows of dirty windows and the patchy yard below mean safety, just like the first time she saw them. Suddenly she’s furious.

She turns slowly, remembering she’d promised herself he’d never frighten her again. The headlights of an approaching car illuminate the street. There’s nothing. Every fibre in her body says he should be standing there, stony-faced and mean, but he’s not.

‘What do you want?’ she screams into the dimness, fists clenched at the shadows. But she’s alone.

The drumming in her chest slows back to a steady beat. Maybe she’s going mad. Somewhere above her the soft form of Petey is waiting.

Isobel

ISOBEL STARES AT THE PHOTOGRAPH of the man and tries to feel something other than minor distaste. The blank eyes and rough skin don’t make her recoil, even though she knows what he’s been accused of. Instead she spots her thumbnails at the edges and thinks vaguely that it’s time to book another manicure.

She shifts in her chair and stares at the wall of glass beyond her desk. If she stood in front of it, as she does sometimes, she would see the city stretched in all directions below, lines of traffic inching along its streets. But she doesn’t, and all she can see is a block of murky morning sky.

She puts the photograph down and listens to her colleagues arriving for the day, the artificial call of computers being switched on and snippets of conversation. Bernard asks Penny, the receptionist, how her weekend was, before Madeline, the paralegal, butts in about the photocopier. Their banter is irritating. Isobel’s been in since daybreak.

‘It needs a new cartridge,’ Madeline continues.

‘Good luck with that,’ Bernard laughs.

He should really stop sauntering in with the admin staff each day if he wants to be taken seriously. Easy charm only goes so far; there’s more to this job than being personable.

She pushes a slip of hair behind her ear and tries to ignore the fact he reminds her a little of her mother, guileless with something sharper beneath the surface. It makes the chatter more irritating.

‘Some people work to live, Bel. It’s not always the other way,’ Marcus s

aid to her as they got ready for bed one night.

He was able to reduce things in a way that both irked and consoled her, creating a small tug of war in her chest.

She arranges the file notes on her desk and contemplates closing the door as Malcolm does his morning rounds. He is operatic in asking about Madeline’s Saturday night. She replies, too loudly as usual, that it was awesome. It won’t be long before she realises that doing the rounds is Malcolm’s way of keeping a tab on things and she’d best tone it down.

Knowing this is gratifying. After almost a decade at Wesley and Hoop, Isobel’s finely attuned to the place. She knows, for instance, that despite Malcolm’s bravado, the other partner, Andrew, has the last say. She knows too that Penny runs off reams of colouring-in pictures for her daughter after work, that Bill the cleaner uses the staff espresso machine before his shift each morning and that Bernard has a diary of their colleagues’ birthdays on his computer. He showed her once, leaning in close to point hers out.

She wonders at times what her colleagues know about her, apart from the facts. The old guard will remember how quickly she was promoted to senior lawyer. And anyone could tell you she sweats buckets for the place. Some nights her head barely touches the pillow.

Luckily, Marcus understands. It’s one reason their marriage works. They want the same things, and mainly got them too. The house, a stone’s throw from the city, with a second one on the coast. The hard work pays off. It’s lonely at times, of course, but long hours at the firm mostly keep her doubts at bay.

The winter sun breaks through the clouds for a moment, streaming across the ash grey carpet, past the filing cabinet to the sickly pot plant in the far corner of the room, where it casts a leafy shadow on the wall.

She watches it, picks the photograph up again and lets the office drop away. The air sharpens and she begins to notice small details that might support her case. Beneath the man’s roughly shorn hair is an old scar, an injury inflicted in childhood perhaps, a small vulnerability or sign of abuse that might garner sympathy.

She doesn’t doubt he’s committed the crime, but it’s her job to defend him, even if he is an evil bastard. Over the years she’s learnt to push everything else aside. She’s defended men in expensive suits accused of assaulting their girlfriends, violent hooligans and youths who thought they were invincible until they finally knocked a family of five off the M1.

This client is the genuine article though, a real piece of work. He should sicken her but men like him keep her in business. Plus, it gives her a secret thrill to be so close to danger, satisfying a part of her that money and comfort certainly can’t.

The phone on her desk lights up before Penny announces that her mother, Grace, is on the line.

‘Ask her to wait,’ she tells Penny, annoyed at the interruption. These calls have a way of making her feel guilty and slightly unsettled. So her mother waits, a flashing light, while Isobel orders the papers on her desk.

‘Belly?’ she asks when Isobel finally picks up the phone.

Isobel stares out the window again as the sun retreats behind a cloud.

‘Yeah, it’s me, Mum.’ She hopes her tone will hurry things along.

‘I’ve tried calling a few times …’

‘Mmmm.’ She doesn’t want to explain again how busy work is.

‘I’ve got news.’

Isobel readies herself for an update on her father’s thriving tomato crop or the neighbour’s recent lotto win. She puts her mother on speaker, places the receiver in its cradle, and turns back to her desk to search for a witness statement.

Her mother mentions something about her pancreas.

‘Can’t they give you medication for that?’ Isobel frowns, sure the statement was here a minute ago. ‘Antibiotics?’

Silence.

Then: ‘It’s terminal, sweetheart.’

She uncovers the statement, reads the first two words and drops it again. ‘What?’

Her mother repeats herself slowly but this time Isobel doesn’t reply, wanting only to hear the sound of her mother’s breath on the end of the line.

In front of her, beside the witness statement, is the mugshot of her client. He stares back with flat blue eyes. She thinks of the homeless girl they found at the playground near his house, then of the way Grace would tuck Isobel into bed at night, tight corners so nothing could harm her.

‘I’ll call you back,’ she blurts, because it’s all she can manage before she hangs up, stumbles to the bathroom and locks herself in.

When she finally emerges, she walks stiffly back to her office and closes the door. Then she picks up the phone again and dials Marcus’s number. When he finally answers, she blurts out that she wants to go ahead with IVF after all.

Rosie

‘PETEY.’

She pops a crumpet in the toaster and takes an apple from the fruit bowl, chopping it into eighths, the way he likes it. He’ll check the number carefully when his teacher announces fruit break.

She pictures him laying each crescent slice on the table in front of him, while the other kids wolf down their orange segments and watermelon chunks and get back to work. If it’s cut wrong, he’ll be upset.

‘C’mon, mate, I’ve got to drop you at Mr Granthall’s.’ She drains her tea, picking a stray leaf from her mouth, and leans for a moment against the tiny bench before heading to his room.

She can’t blame him for being slow, she thinks, booting the wall heater on the way past. Dulcy asked her to work late at the store last night, so he was at Mr Granthall’s until bedtime.

‘Petey.’

She sits on the edge of his bed and rubs the leg hanging out. There are soft white hairs on it now and it’s cold to touch. The room is freezing too, like the rest of the dump they live in, and a world map on the wall opposite is beginning to droop. When she talks, steam mists from her mouth. She’ll have to drop past the maintenance office beneath the flats on the way to TAFE to tell them about the heater again.

When Petey’s finally up and ready, they walk along the narrow concrete landing to Mr Granthall’s place three doors down. Children’s screams float up from the school ground beyond the yard at the bottom of the flats, capturing Petey’s attention. He stops while she walks on, trying to work out which train then tram to catch to make class on time.

Churchill whines on the other side of Mr Granthall’s brown door. She waits for the inevitable shove in the back from Petey in his rush to get to him, but it doesn’t come. She huffs as she turns, then freezes. Petey’s perched on the shiny metal railing, his legs dangling over the other side, his backpack poking out. He looks down at the ground far below then shouts, ‘Hey!’ in the direction of the schoolyard.

‘Petey,’ she says softly, so not to scare him. ‘Get down, mate.’

He ignores her. She wants to run over and grab him, pull him backwards so he falls the right way, but what if he lets go?

She edges slowly towards him. ‘Time to go, mate. You can say hi when you get to school.’ She tries to keep her voice steady. ‘Churchill’s waiting.’

He starts rocking at the name. ‘Churchy, Churchy,’ he shouts before turning to give her a big grin. It’s enough to make her lunge, to grab him by the pack and yank him backwards. He falls to the landing with a thump. The pack breaks his fall but the shock starts him wailing.

Fear then anger rise up from her gut. ‘Don’t you ever do that again.’ She tries to help him to his feet. ‘Ever!’

The yelling makes things worse and he flails at her, trying to keep her at bay. It takes everything she has not to fight back, not to grab him hard and make him promise. But it’ll only make things worse. She steps back instead, gives him some space and waits it out.

Finally, she puts a hand on his arm. It shakes a bit, making her guilty. It ambushes her every time, an ugly pang that makes her throat constrict. Sometimes living with Petey’s like being on a show ride. It’s hard to keep up.

‘It’s okay, mate.’ She pulls him close

, nestles her chin in his hair. ‘I just didn’t want you to fall over.’

‘Sorry, Mum, sorry,’ he says over and over into her jacket, until there’s a wet patch where his mouth is and he wants her to let go.

Behind the door, Churchill starts to bark.

‘Go on,’ she says, forcing down the last of her anger. ‘He’s waiting for you.’

Mr Granthall unlatches the doggy flap and the fat little dog shoots out like a cannonball. Then he opens the door. ‘Here’s trouble,’ he calls croakily after Petey and the dog as they bound inside. Petey turns and salutes him before disappearing around the corner.

‘All right, Rose?’

He’s the only person she lets call her Rose.

‘Think so,’ she exhales without explaining. Mr Granthall understands. His nod is enough to send a wave of relief through her. Some days she just wants to drop Petey off and walk away. Mr Granthall never makes her feel bad for it.

She pulls a crumpled envelope of cash from her pocket to hand to him.

He ignores it and adjusts his knitted beanie. ‘Got that heater fixed yet?’

‘It’s a work in progress.’

He nods and she notices how milky his eyes are. It’s easy to forget he’s ancient.

‘Go buy yourself one of those portable jobs,’ he says, nodding at the envelope. ‘The oil ones are best.’

Rosie shoves the envelope back in her pocket and smiles. ‘Sure you’re right getting him to school?’ She peers over his shoulder into the dusky hall lined with black-and-white photographs.

He snorts with indignation. ‘Shouldn’t you be at TAFE?’

She nods and calls to Petey. ‘Bye, mate.’

‘Bye, Mum, bye,’ he shouts back, as if nothing has happened.

Seeing Petey hanging unsteadily in space sets her on edge and she takes the stairs to the yard two at a time. He’s getting big, and it’s getting more difficult to keep an eye on him. It scares the shit out of her sometimes. One day, not too far away, she won’t be able to pull him off the landing rail; he’ll have to talk himself down.

She stops at the bottom of the stairs and leans back against the patchy, graffiti-stained wall. Above her, other residents knock about in flats just like hers, getting ready for the day. Techno blasts from one, and somewhere even further up a baby screams blue murder.

Small Blessings

Small Blessings