- Home

- Emily Brewin

Small Blessings Page 2

Small Blessings Read online

Page 2

Mostly the noises are comforting, filling her head so she can block out the loneliness. But today it’s suffocating and she wishes she were someplace quiet with an uninterrupted horizon. She pushes her fists into her eyes as her phone rings.

She gets to it just before it rings out. ‘Hello?’

Nothing.

Then she hears breathing, faint, like air coming through a thin crack.

‘Hello? ’She checks the screen; the number’s unknown, like yesterday.

When she puts it to her ear again the caller’s gone, and the silence makes her swallow. She holds the phone in her hand for a second then shoves it right to the bottom of her bag and hurries to the dingy maintenance office.

As she reaches the door she thinks she hears Petey’s voice far above. She steps back, looks up and shields her eyes against the bright winter sun. She scans the landings until she finds theirs. But Petey’s not there, of course, and for a moment she wonders if he ever was.

Isobel

SHE WOKE TO LACHIE launching his bony frame onto her bed, his ten-year-old elbows digging through the quilt to poke the sensitive new lumps on her chest.

‘Get off,’ she yelled as he burrowed in next to her. Lately his presence was annoying, the way he badgered her to play tiggy and wouldn’t let her have a minute on her own.

It was a new thing, this desire to be left alone. Some afternoons, on the way home from the beach, she loitered so that Lachie got bored and ran ahead. When he told their mother at dinner once she’d grinned. ‘She’s off to high school soon, duck,’ she said, ruffling his hair. ‘You’re cramping her style.’

‘No, he’s just a pain,’ Isobel nipped back across the table. But it was true. She was starting at Nottingham after the holidays and, although she was excited, her stomach turned soupy at the thought of it. Bernie and Gab and the others from her primary school class were off to Altona High, and she already sensed the distance between them.

‘Think of all the opportunities.’ A few wisps of the coppery hair pinned loosely to her mother’s head had escaped and curled elegantly around her ears. But when she placed a hand on Isobel’s, her nails were chipped and her knuckles swollen. ‘Perks of the job,’ she joked sometimes, but Isobel knew how painful her hands got. They were worse with the extra shifts she’d had to do to pay for new textbooks.

Lachie whined on the bed beside her. ‘Mum and Dad are fighting.’ So she reluctantly let him under the diamond-patterned quilt. They went quiet and listened, big eyes glued to the ceiling.

‘She’s going!’ Her mother’s voice bounded down the hallway.

‘Gracie, think about it. She’s a smart kid. She’ll do well anywhere.’

Isobel’s chest tightened. It wasn’t the first time she’d heard this conversation. All summer holidays had been uneasy with it.

‘C’mon, love, paying those fees, even half of them, is going to be a bloody struggle.’

Her mother’s heels tapped briskly across the floor followed by a clash of crockery in the sink, then silence.

‘Look at my hands, Jim,’ she said finally.

Isobel pictured her holding one out, red and scaly, forcing her father to accept it. She pictured him taking it gently, an admission of defeat, because it was hard to say no to Grace Taylor once she got an idea in her head.

‘Things will be different for her.’

Even at twelve and a half, Isobel knew it was unreasonable. Marie down the road was at university and she’d gone to Altona High, but her mother wouldn’t let it go. Isobel knew it, and so did her father.

‘Breathe,’ Isobel reminds herself as she turns onto Millers Road, still chased by last night’s dream. Her mother, young and playful, had run into the surf then disappeared beneath a wave. It was the same two nights ago, and the night before that. In it, Isobel sat on the beach, digging her toes into the hot, hot sand, waiting for her mother to resurface. Deep down she knew that she wouldn’t.

The journey to Altona is depressing. The further west she drives into the ugly sprawl of deserted shops and messy suburban yards, the greater the crush in her chest. It presses, threatening to but never quite snatching the air from her. It’s taken exactly three days to find the courage to visit her parents. Each one has been harder to breathe through.

She pulls up outside the front of the house she grew up in and sits for a while. Everything appears normal, from the fire-engine red letterbox on the gatepost to the garden gnome next to the steps. Even the lawn is still mown to within an inch of its life. For a moment she’s fooled into thinking things are all right. It’s enough to make her unclip her belt and climb from the car.

‘Come in, pet.’ Her father ushers her through the front door into the long wallpapered hall with a hand on her arm.

She kisses the air near his cheek, clearing her throat at the faint scent of fried food, like the fat sausages her mother used to cook for tea. The thought of them, splitting down the middle to spill their soft pink insides, still makes her nauseous.

‘Good to see you,’ he says wearily, brushing back his bush of grey hair. ‘It’s been a while.’

Isobel follows him down the hall to the kitchen. She wants to say that time flies, that in her world three months can pass with the blink of an eye, but he wouldn’t understand.

‘Mum wanted to make you something,’ he rubs his big nose with the back of his hand, ‘but she was buggered, so I told her to take a kip.’

Isobel nods, secretly relieved. The orange-tiled kitchen smells like the meals of her childhood, of meat and three veg boiled or steamed and smothered in butter and salt.

‘I’m glad she didn’t go to the trouble.’

Her father considers her for a moment longer than is comfortable then leads her past the sage green formica table they used to eat around to the lounge room. ‘She’s here, Gracie.’

Isobel tries to ignore the neat rows of photographs of Lachlan and her at various stages of childhood that line the wall above the mantle opposite. There’s only one of her as a teenager. It was taken on her first day at Nottingham Girls, her hair in pigtails, a smile on her face that was too big to last. She refused photographs not long after that. And there’s nothing of her again until the large sleek wedding shot she had framed and delivered sixteen years ago. It hangs next to an awkward teenage Lachie, staring pensively into the lens.

He lives in Sydney now with his partner, Mateo, and only comes home every second Christmas. She can’t blame him, really. He’d stuck out on the mean streets of Altona, a sensitive boy who’d rather draw than play footy. He never stayed long when he visited, escaping back to the relative safety of Potts Point. It was a long time since either of them had fitted in around here.

Isobel steels herself before rounding the worn leather couch to find her mother. The sight of her, half the woman she was three months ago, forces Isobel to a halt.

‘Mum,’ she says sharply, as if asking a question, before brushing her mother’s forehead with a kiss. ‘You look …’

‘Bloody skinny.’ Her mother laughs, adjusting the crocheted blanket on her lap, her signature red lipstick flawless despite it all.

Isobel sinks into the recliner opposite, ridiculously grateful that her mother is still going to the effort. ‘Well …’

She glances around the room for inspiration but everything she sees makes it harder to speak. The ancient telly perched on a small wooden stand, the glass coffee table scattered with trashy magazines between them, the formica table and the dingy kitchen beyond.

‘How are you?’ her mother cuts in.

Isobel tucks a strand of ash-blonde hair behind her ear. Maybe small talk will avoid the fact her mother is wasting away in front of her. ‘Fine.’

‘Cuppa?’ her father calls from the bench separating the kitchen from the dining area.

Tea was the only reason he ever ventured in to the kitchen. But Isobel realises with a start that he must be helping with the cooking now. A prospect that seems wholly ridiculous.

; The kitchen with its pine-panelled cabinets and laminated benchtop was always her mother’s domain, when she wasn’t working at the cable factory, the same way the shed was her father’s when he wasn’t at the refinery. That’s how the world was organised then, simple and predictable.

On Sundays her mother would pack a picnic lunch and the whole family would walk to the beach. These were the times she loved best as a child, the sand gritty between her toes while Lachie laughed at her from their father’s shoulders.

Her mother arches an eyebrow then rests her head back. Her hair looks unnaturally flat. Thick, long and wiry, it has had a life of its own for as long as Isobel can remember. As other women aged they cut their hair into respectable bobs, but not Grace Taylor. She simply pinned it back the way she always had, so it formed girlish grey ringlets around her ears.

The kettle whistles in the kitchen then splutters as it’s taken off the stove. Isobel turns to it, hoping her father won’t be long.

‘Jim,’ her mother calls abruptly.

‘I’m sure he can manage a cup of tea on his own, Mum,’ Isobel says, regaining some composure.

Her father bustles in, clutching a packet of Monte Carlos. ‘What’s wrong, love?’ He puts the biscuits on the coffee table and goes to her.

She shifts, squeezing her eyes shut so that her lids are thin and plum coloured.

The years melt away as he bends to meet her face. Suddenly Isobel is small again, watching them fold into each other while the world spins on without them.

A groan brings Isobel back. Her father strokes her mother’s cheek with a rough finger. ‘I’ll get you something,’ he says before hurrying from the room.

Isobel uncrosses her legs and leans slowly forward. Her mother’s lashes are sparser than usual and when she opens her eyes they have the look of an injured animal, needy and slightly reproachful.

‘Maybe you’re hot.’ Isobel yanks the blanket and it drops to the floor. She gets up, fumbling to unhook it from the bottom of the couch before repositioning it crookedly across her mother’s lap.

If it were the other way around the job would be done effortlessly, the same way her mother cooked casseroles for grieving neighbours and rubbed Vicks into the soles of her sick children’s feet.

After each late shift, she’d sneak into their bedrooms to stamp their faces with kisses. Later, it became suffocating. Later, Isobel wanted a mother who was less … how could she put it … passionate. A mother who didn’t fill whatever room she was in with airy laughter and conversation; a mother who attracted less attention, who wasn’t so full of life; a mother who listened and fitted in so she could too.

Guilt drains through her chest. She should have been more careful what she wished for.

Her father rushes into the room with a glass of water and two small white pills pinched between his fingers. He slips them into her mother’s hand, holding it until her fingers close. Then watches as she swallows.

Isobel stands, arms dangling helplessly at her sides. It’s not a feeling she’s used to.

‘You’re right, pet,’ her father says, spying her there.

She nods.

Her mother smiles unevenly at them, but her lipstick’s smudged and there’s a thin film of perspiration below her hairline that makes Isobel flinch.

Rosie

‘DID YOU DO the homework?’ She nudges Skye as she pulls her textbook from her bag.

‘Yeah. I did the chapter where the English lady gets stuck in the cave.’

‘Mrs Moore.’ Rosie bites her lip and pulls the sleeves of her hoodie over her hands. She read A Passage to India by a bloke called Forster in one night. The next morning it felt like someone had run sandpaper over her eyeballs, and a line about the caves kept spinning like a top in her head.

‘Nothing is inside them, they were sealed up before the creation of pestilence or treasure; if mankind grew curious and excavated, nothing, nothing would be added to the sum of good or evil.’

Rosie had contemplated the nothingness. It was hard to wrap her head around, like trying to imagine the edges of space. She wrestled with it as she lay in bed before finally surrendering. Maybe there was no answer. A surprising sense of calm had claimed her then so she slept like a log. But the feeling ebbed away overnight and she woke uneasy.

She’d thought about it while she packed shelves at Dulcy’s that day and cooked rissoles for Petey’s tea and while she was running for the train as it left the platform, but she didn’t do the analysis.

‘You?’ Skye asks, lash extensions fluttering like two small fans.

She shakes her head, concentrating on the neat lines in her exercise book.

Around the sparsely furnished room her classmates scribble notes and chat about the weekend they had. They’re old and young, suited and scruffy, all here, like her, to finish year twelve. She hasn’t asked them why. Hasn’t got the energy to swap stories, couldn’t hack their sympathy even if she did.

Once on the train, a lady offered her money to help look after Petey. ‘It must be hard,’ she’d said holding out a twenty, gesturing at him while he loudly counted the squares in the seat fabric. ‘I feel for you.’

Rosie wanted to tell the woman to shove her money but Petey glanced up, so she took his hand instead and dragged him off at the next stop.

Skye stares with wide blue eyes, as if expecting a better explanation.

‘I’m going to hand in last week’s homework, the book review.’ Rosie brushes her fringe back. ‘I didn’t get time to do the analysis.’

Skye pats her arm. ‘Danny’ll be cool.’

Danny, their English teacher, is a hipster. Skye’s got a crush on him. She cocks her head and flashes him her perfect smile whenever he walks past.

‘He’d be cool if it was you.’

Skye giggles. But it’s not funny. Things have been good, she’ll kick herself if she fucks it up. Petey needs her to finish year twelve so she can get a decent job. Sometimes she thinks about applying for uni but it seems like a pipedream.

She never really tried at high school. It wasn’t that kind of place. And it’s not like she had a decent role model. Her dad disappeared before she turned two and Vera’s idea of a good education was being sober enough to drive her to school.

She goes to TAFE so she can give Petey a better life one day. So he can be proud of his mum, instead of ashamed.

‘Right, kids.’ It’s Danny’s joke. Kinda funny too, considering he’s younger than most people in the room. ‘I’m coming around to collect your analysis. We’ll spend the rest of class working on our characters.’

Rosie puffs out her cheeks. She’s doing her best to be responsible but it’s hard.

‘Yours, Rose?’ Danny says as Skye smiles at him.

‘It’s Rosie.’

He shrugs.

She thinks of Petey curled up in front of Mr Granthall’s heater watching the telly. Warm at least. He won’t mind if she’s late.

‘Can I do it now?’

Danny considers her through his dark-framed glasses, tapping the papers against his leg.

‘Go on, Danny. She’s a single mum.’

Rosie flushes with anger. The last thing she wants is the teacher being soft on her in front of the others.

Skye squirms and fiddles with the thin silver chain around her neck. ‘Sorry.’

Some of their classmates turn to watch and Rosie’s shoulders tighten.

‘I’ll cut you a deal,’ Danny says. ‘Hand the analysis in by the end of class and I’ll forget it was late.’

Rosie glances at her hands then, nails bitten to the quick. ‘Well, technically it wouldn’t be late.’ She challenges Danny with a look. ‘It was due today.’

Isobel

HER HUSBAND WAS WEARING A DRESS the first time she met him. A red frilly number, something a cabaret dancer or a prostitute might wear. His long hair was pinned in a crooked French roll and rouge stained his cheeks.

His loafers, fashioned from good-quality leather, were th

e one reassuring feature. She kept an eye on them while they talked, leaning into the bar at the law faculty party.

‘You must really like my shoes,’ he said finally, smearing lipstick as he drank his beer.

She blushed, lost for words and annoyed she’d come. Costume parties weren’t her thing, but apparently this one was a good networking opportunity. It was her final year and she needed all the help she could get.

‘They’re very nice,’ she replied. And they were; well, expensive at least. She could tell. She made a point of knowing quality when she saw it. Her own wardrobe, in the dinky house she shared with two other girls, was sparse, but the few clothes she owned were solid investments. She was going to be a lawyer, after all, so she figured she’d better play the part.

Her housemates teased her about it as they slipped on their tatty Converse sneakers and ripped jeans, but they didn’t have anything to prove. They had parents who paid their rent and topped up their bank accounts.

She drained her vodka and orange when Marcus mentioned his family’s holiday house in Sorrento and accepted another.

‘So, what are you studying?’

‘Bridge building,’ he answered with a crooked grin.

It was disappointing. She was surround by lawyers and here she was talking to a tradie, just like her dad.

‘Well, not building, exactly. Designing them. Engineering.’

She perked up.

As the night wore on she waited for him to leave her for somebody fun, the girl in the playboy bunny outfit perhaps or the French maid. She wasn’t even in costume. Dressing up made her cringe. She glanced around the bar while he chatted. One of her housemates was playing pool with a sailor; the other had disappeared into the toilets with a Smurf.

‘I love the longevity of bridges.’ Marcus swayed enough to make her step out of his way. ‘They’re solid, reliable, you know?’ He raised his pint glass. ‘A good bridge lasts centuries.’

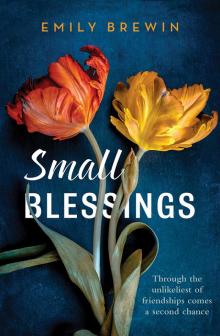

Small Blessings

Small Blessings